Who is in the News: Meet the man behind Dark Matter Labs, who has radical plans for a greener future.

‘The scale of what we’re about to face is completely underestimated’

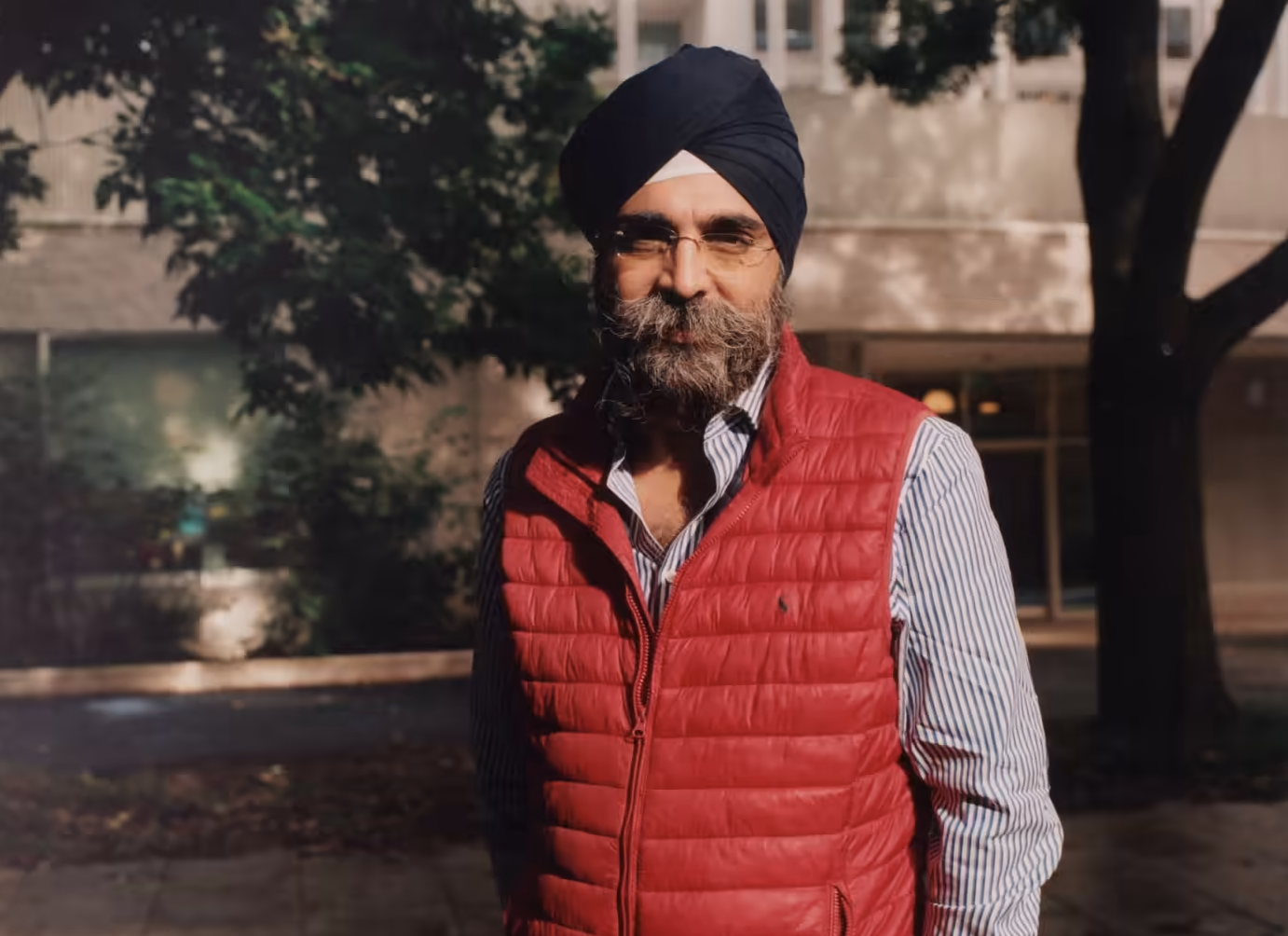

Architect Indy Johar © Harry Mitchell

Architect Indy Johar's interview with The Financial Times

The thing about dark matter is that you can’t see it. Even the most sophisticated machines cannot detect it. Yet it constitutes about 27 per cent of everything in the universe. It is, you might think, the opposite of architecture, that most tangible of the arts; solid, visible and unmissable. Which, I suppose, is exactly why architect Indy Johar chose the name for Dark Matter Labs, a highly unusual, interesting and influential not-for-profit architecture practice that few people seem to have heard of.

Johar is jovial, persuasive, engaging and visionary, dressed in a turban, gingham shirt and gilet. His salt and pepper beard and luxuriant moustache cover a mouth that forms words a little too fast for my brain. Johar won this year’s Design Innovation Medal at the London Design Festival, a rare moment of recognition for an architect whose practice is so diffuse and perhaps, like dark matter itself, difficult to comprehend.

“The scale of what we’re about to face is completely underestimated,” Johar tells me. “I think we’re going to have to redesign everything around us, our clothes, our food, our furniture, what we value, what the price of goods is, who owns matter, how we value durability and resilience, how we shift to an intangibles economy over a material economy?’

“The economic geography of our places and the way we live is fundamentally changing,” he continues. “The structure of society, our theory of work in a machine-assisted environment is changing and at the same time we need to transform the relationship with energy, so we’re in a structural transition of pretty much everything around us. It’s something no civilisation has ever faced before, a class of challenges which can only be solved on a planetary scale.”

Johar helped launch the WikiHouse project that develops open-source, low carbon homes

To make these problems less abstract, Johar suggests we look to something more tangible. “That whole sense of planetary entanglement,” he says, “might manifest itself in a house.”

He explains: “Where do the materials come from? Where is the embodied carbon? Who owns the waste of materials at the end of life? Who owns the butterflies in your garden? That is the great design transition.”

Butterfly ownership might sound ephemeral but that is, perhaps, precisely the point. Johar suggests that everything down to the smallest detail should be reassessed. That is a very identifiable form of architectural thinking, the ability to home in on the details and see, simultaneously, the micro and the macro scales of world building. But, despite being recognised with this award, he is uneasy about being at the centre of any story.

“For me this is not about one designer, it’s about the fundamental deep reimagination of our world. We’ve been living in a 400-year-old vision of our world based around Newtonian physics and Cartesian logics, based on separation of object and subject. Now we’re starting to see the world in terms of entanglements, interdependencies, externalities, a re-entangling of the world at a philosophical, material, social, liabilities and cost level.”

There is no single way in which Dark Matter Labs is attempting to address these planetary issues. Over the years, a raft of proposals and models has emerged, each using leaps in technology to understand possible futures. With an earlier organisation, 00, Johar was a co-founder of WikiHouse, an open-source digitally manufactured system that allows people to build low-carbon homes. He has worked with corporations and cities, he works with start-ups and accelerators but also critiques the models of corporate capitalism. His understanding of the world might be at a planetary scale but his concerns are with bureaucracy, the rules of engagement and for what he calls a “boring revolution”.

Johar is an architect who does not arrive with seductive designs or visionary drawings, but rather a set of proposals for reimagining our institutions and our tool kits for different kinds of economy and relationships. And this is no boutique, post-grad quirk: Dark Matter Labs is a 60-strong office with bases in Canada, the Netherlands, South Korea and Sweden as well as London.

Johar says that architectural practice must simultaneously see the micro and the macro scales of world building © Harry Mitchell

He favours techniques that come from technology. If the financial markets are now largely conducted by computers communicating with each other at lightning speeds over tiny transactions, why could this not be applied to this new set of relationships? Whereas much thinking about the green economy, zero carbon and a post-capitalist utopia seems woolly and naive, his contentions work within the systems of exchange, using their capacity for complexity, technology and markets to build in real costs.

Dark Matter Labs is currently working on an array of designs that might present models for the future. Johar cites a programme for a canopy of trees in Glasgow, greenery conceived as infrastructure. Trees are currently framed as costs rather than assets, he suggests. “Yet it’s been shown that trees can reduce temperatures by up to 12 degrees, and there are savings in reduced road maintenance, health impacts, reduced levels of asthma, reduced flood risk . . . ”

Even the biggest of ideas can come down to a simple seed. And Johar is engaged with the big ideas. “We could think of the Enlightenment meeting the Entanglement. Quantum physics recognises that entanglement. There are also parallels with indigenous thinking methods, how we live with the land.”

If the Earth is about to pronounce its judgment on the short experiment of the Anthropocene, we had better strap in. Johar’s proposals are not the seatbelt or the airbag but the brakes, the mechanisms to reduce our speed towards that destiny. Wide-ranging and fascinating, he is, perhaps, the architect who could have the greatest impact on how we understand our systems of exchange, exposing the real costs of things. With barely a building in sight.

This article appeared in The Financial Times in November 2022.